Royal Corps

of Signals

Dud's

Army.

Chapter

12

Bugs and Bunnies

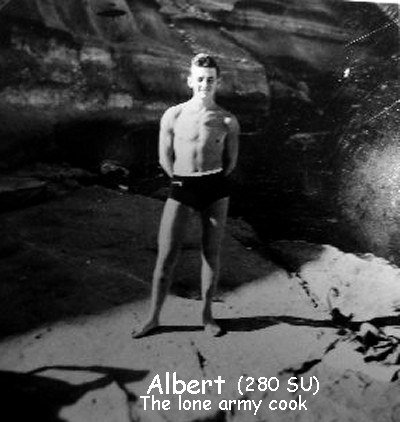

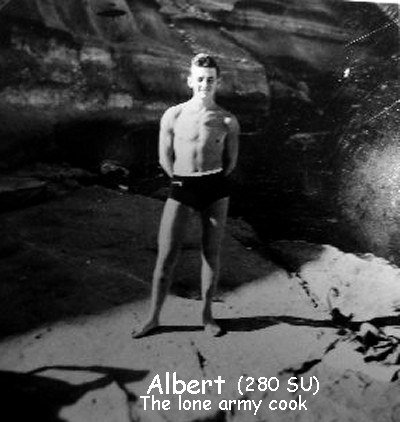

Having arrived in Cyprus during the early winter months there

was time to more casually accustom oneself to the higher temperatures along

with getting a tan started ahead of the summer. One of the trademarks of a newly

arrived nig-nog was his lily-whiteness, contrasting unhealthily with the tanned

long-timers. This new-boy pallor would provoke the call to “Get yer knees

brown, matey.” No question the sun shone to strong effect in Cyprus. Albert

The Lone Army Cook, for instance, initially took to naked sunbathing which resulted

in a serious sunburn to his more precious parts. He needed hospitalisation to

bring him back to rights. One would have thought that a trained cook would not

have been so silly as to roast himself, but to be sure, vanity and sanity have

only a common rhyme to connect them.

A further tell-tale, nig-nog characteristic at Cape Gata was

to appear at the swimming place covered in red blotches - a sure sign of the

visitations of bed bugs. These suckers not only infested mattress crannies but

also established colonies in the wooden walls the blokes were encouraged to

build around their tents. At the end of the day as darkness fell the bugs could

actually be observed marching out in orderly columns from their daytime retreat,

deploying for attack in perfect formation. It was obvious from their precision

of march they were Army bugs and naturally they favoured the soft white bodies

of nig-nogs. The fellows who regularly went swimming were not sucked on, probably

due to the sea-salt on their bodies. Periodically every inch of one’s

mattress had to be scrutinised and the tent walls sprayed with DDT. The whole

camp regularly went to war against bed bugs but they proved a stubborn and elusive

enemy. It never occurred to anyone in management to prohibit the tent’s

encirclement of nailed up boards.

Life at 280 SU settled into a routine of eat, sleep, work and

play, the latter providing the dominant interest for us Radio Relay types. Very

occasionally there came a need for two of us to drop one of the sixty-foot high

Yagi antenna, for example, which we brought down and re-erected using the cantilever

method invented by Archimedes. The only other job comprised changing the oscillator

crystal in one or other of the AN/TRC sets and retuning - a half-hour’s

concentration at most. Considering we had trained for eight months prior to

our posting one might suppose we were a shade over-qualified and a deeper shade

under-worked. But if there were management rumblings over the few hours we were

at our post and the very little we did during those hours we were not privy

to such noises. Without fail we maintained the critical RAF phone channels open,

day and night, ad infinitum, and this net result of Army presence seemed to

be sufficient.

I

had not done a month’s worth of shifts before discovering the presence

of rabbits. At least I supposed the creatures were rabbits although they might

have been hares. Their ears were longer than British rabbits but in all other

respects they seemed quite standard. They frequented the area of bush between

the back of our equipment hut and the barbed wire perimeter. There was nothing

for it but to immediately consider the prospect of rabbit pie. Albert expressed

full support for the notion and would provide the bacon, onion, apple, bay leaf,

suet crust and oven time in the event I could provide the elemental ingredient.

So, as Mrs Beeton famously remarked, and eventually wrote down in a book: “First

catch your rabbit.”

I

had not done a month’s worth of shifts before discovering the presence

of rabbits. At least I supposed the creatures were rabbits although they might

have been hares. Their ears were longer than British rabbits but in all other

respects they seemed quite standard. They frequented the area of bush between

the back of our equipment hut and the barbed wire perimeter. There was nothing

for it but to immediately consider the prospect of rabbit pie. Albert expressed

full support for the notion and would provide the bacon, onion, apple, bay leaf,

suet crust and oven time in the event I could provide the elemental ingredient.

So, as Mrs Beeton famously remarked, and eventually wrote down in a book: “First

catch your rabbit.”

One knew how to catch rabbits and one had done so since fourteen

years of age. One could net the burrows and slip in the ferret, or net along

the brambled railway embankments and use the village dogs to drive them out.

One could go out in the early morning or late evening and shoot them with either

a four-ten, a twelve bore or even a catapult. And one could set snares wherever

the rabbit commonly runs. As an impecunious sixteen-year-old I had employed

this latter method to good advantage, selling my goods at two-and-sixpence each.

But in camp there were no ferrets, dogs, nets, catapults or shotguns; it would

have to be snares. And lacking an ironmonger’s shop, they would have to

be manufactured.

A proper snare, or slip as it is called in Newfoundland, is

fashioned from braided brass wire with an eyelet of the same material at one

end to assure the wire clean travel. There was no braided, brass wire in camp.

I settled for braided, copper wire which is inferior to brass in this application

by token of its lack of spring and tensile strength, but I made them up all

the same, using brass eyelets taken from my football boots. The runs through

the bush were easy to recognise and it was with high hopes I set my loops in

the most promising, well-travelled courses. Yet try as I might those Cypriot

rabbits outfoxed me, so to speak, and I never succeeded in catching one. On

returning to my traps I found my loops dismissively brushed aside. Not accustomed

to failure in this pursuit one concluded that either the creatures’ inordinately

long ears or excessively bouncing gait confounded the scope of the slip no matter

what diameter or distance above ground level I arranged them.

Failure in this enterprise was no great loss to me but Albert

was disappointed, the chance of his bringing off such an elegant dish at the

Cape Gata cookhouse coming infrequently. Further, producing a rabbit pie from

one’s hat, so to speak, would have gone far to restore the damage done

to his psyche as a result of the still-rankling, sun-burning debacle of last

summer. I felt badly for Albert and figured if I could contact someone in the

motor pool and thereby acquire an old rubber inner tube I’d have the necessary

propellant to make a catapult. I was an excellent shot with this weapon. But

while thus engaged in solving my rabbit problem, a call came through for me

to pack up and prepare for a sojourn in a Signals camp to the west of Episkopi

called Paramali.

Home

.

I

had not done a month’s worth of shifts before discovering the presence

of rabbits. At least I supposed the creatures were rabbits although they might

have been hares. Their ears were longer than British rabbits but in all other

respects they seemed quite standard. They frequented the area of bush between

the back of our equipment hut and the barbed wire perimeter. There was nothing

for it but to immediately consider the prospect of rabbit pie. Albert expressed

full support for the notion and would provide the bacon, onion, apple, bay leaf,

suet crust and oven time in the event I could provide the elemental ingredient.

So, as Mrs Beeton famously remarked, and eventually wrote down in a book: “First

catch your rabbit.”

I

had not done a month’s worth of shifts before discovering the presence

of rabbits. At least I supposed the creatures were rabbits although they might

have been hares. Their ears were longer than British rabbits but in all other

respects they seemed quite standard. They frequented the area of bush between

the back of our equipment hut and the barbed wire perimeter. There was nothing

for it but to immediately consider the prospect of rabbit pie. Albert expressed

full support for the notion and would provide the bacon, onion, apple, bay leaf,

suet crust and oven time in the event I could provide the elemental ingredient.

So, as Mrs Beeton famously remarked, and eventually wrote down in a book: “First

catch your rabbit.”