Royal Corps

of Signals

Dud's

Army.

Chapter

17

The Noble Duke of York

When two warring parties call a truce it is not because they

wish to stop killing each other but to gain time to improve their resources

for more efficient killing later on. A truce is no more than a metaphorical

breather, a time out, a break between rounds. It is the knock-down and counting-out

that ends the conflict, not the truce. So when the General Emergency was relaxed

both the British and EOKA began taking measures against the next period of conflict.

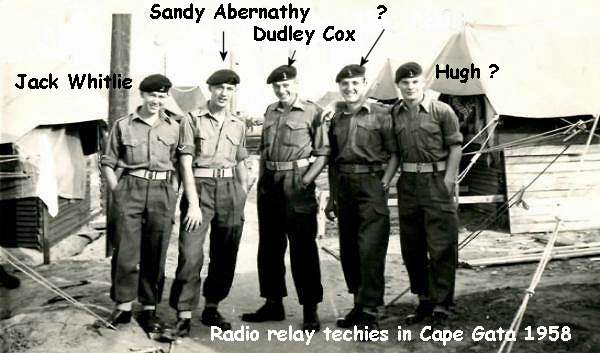

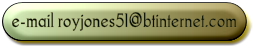

For us army blokes at Cape Gata, although we were not classified as non-combatants,

our superiors must have perceived us as insufficiently combative because orders

came through to the effect that one’s killing skills were to be upgraded.

We were to practice shooting guns.

As

a consequence, one sunny morning Jack and I found ourselves in Akrotiri booking

out Stens, one each this time. We were in the company of clerks, cooks, technicians

and other similarly peaceable types, holding our ten-and-sixpennies like they

might explode at any moment. An officer and a sergeant took charge of us. We

squeezed into the back of a large, canvas-covered ghari and motored south. From

our glum expressions one might imagine we were off to the front. Quitting the

tarmac we entered the bush, dust enclosing us. Morale was low. When we stopped

and alighted we were formed into a two-line squad and marched off down a narrow

track that eventually gave way to open rocky terrain with the sea arcing beyond.

We were high up, where the views were spectacular, eventually reaching the cliff

edge. We had been on foot for about a half hour. There were ragged posts placed

in a row spaced six feet or so apart. Cardboard targets the shape and size of

a human body had been brought and they were now fastened, one to each of the

tilting posts. Our bullets, if fired at the targets with a level trajectory,

would end up going over the cliff and into the sea. There were no boats to be

seen below.

As

a consequence, one sunny morning Jack and I found ourselves in Akrotiri booking

out Stens, one each this time. We were in the company of clerks, cooks, technicians

and other similarly peaceable types, holding our ten-and-sixpennies like they

might explode at any moment. An officer and a sergeant took charge of us. We

squeezed into the back of a large, canvas-covered ghari and motored south. From

our glum expressions one might imagine we were off to the front. Quitting the

tarmac we entered the bush, dust enclosing us. Morale was low. When we stopped

and alighted we were formed into a two-line squad and marched off down a narrow

track that eventually gave way to open rocky terrain with the sea arcing beyond.

We were high up, where the views were spectacular, eventually reaching the cliff

edge. We had been on foot for about a half hour. There were ragged posts placed

in a row spaced six feet or so apart. Cardboard targets the shape and size of

a human body had been brought and they were now fastened, one to each of the

tilting posts. Our bullets, if fired at the targets with a level trajectory,

would end up going over the cliff and into the sea. There were no boats to be

seen below.

It was explained to us we were to take shots at the target from

fifty feet, thirty feet and twenty feet, twelve rounds from position one and

ten each thereafter, thirty two in total. For the last ten shots we were to

fire while down on one knee, after which the magazines were to be removed, the

gun checked for unused rounds and the bullet holes in the targets counted and

recorded. We were not to move from each firing position until ordered. Forty

cigarettes were to go to the man, or the boy, with the most holes in his target.

No provision was made for a safety-bloke at one’s back for knocking-down

purposes or mention made of the Sten’s propensity for cutting off one’s

finger-ends, by now much-prized for impressing guitar chord positions..

We lined up and, as ordered, periodically blazed away, those

of us not actually firing herded well to the rear, sniffing the cordite like

so many nervous gun dogs. I was one of the last to step forward, finding the

shooting as distasteful as I remembered it from Basic Training. My target offered

a strangely submissive figure, jerking as though with pain when the bullets

hit. When it came to counting the holes in him the sergeant and I had already

tallied thirty-two, with several chest and shoulder wounds yet remaining. When

I pointed this out to the sergeant he told me, out of the side of his mouth,

to clam up. Someone alongside of me had been shooting at my target. I was to

keep quiet about it.

I was awarded the forty cigarettes and acclaimed a sharpshooter.

Did the signalman wish to shoot some more? I declined the offer and took the

fags. The expression “quit while one is ahead “ had not been coined

then, but that was the choice I made. We lined up, the perfect ocean at our

backs and going through the “I have no live rounds or empty shells in

my possession, Sir,” routine as the officer raised the obligatory eyebrow

at each of us in turn. We then shouldered arms and trudged away, leaving the

ragged posts standing in as forlorn a dispersement as we had found them.

On our return march to the lorry, possibly discommoded by our

lethargy, or our lack of fierceness, the officer urged us to sing. We gave him

an army verse of “Hitler has only got one ball,” and a schoolboy

verse of “Bollocks, they make a damn good stew,“ both sung to the

tune of “Colonel Bogey.” I made a try to get “O, The Noble

Duke of York” going, if only by way of a bit of a thank-you to the sergeant

for the ciggies, and simultaneously as a protest against the futility of it

all for us, but as on the road to 4 TR, the song did not get taken up by those

around me. So that was that for singing on the march.

In spite of much singing practice with The Hermits I did not

feel sufficiently buoyant to render “The Noble Duke” solo. As twelve-year-old

boys at Chipping Norton Grammar School we’d sing that song in Mr. Rose’s

music class with terrific gusto, its inherent irony pleasing us no end - probably

because it was about an aristocratic stiff being transparently silly. For whatever

reason, the trip to the Akrotiri cliffs to fire thirty-two Sten gun bullets

at a cardboard figure stuck on a post, and getting falsely awarded a prize for

it, had made me homesick. Maybe the feeling came from being reminded of my getting

caught cheating in the geography exam at Whitchurch.

For the remainder of my National Service I never fired a shot.

And I was returned the service: no-one fired one at me.

Chapter

18

DUD'S ARMY INDEX

PERSONAL PAGES

INDEX

Home

.

As

a consequence, one sunny morning Jack and I found ourselves in Akrotiri booking

out Stens, one each this time. We were in the company of clerks, cooks, technicians

and other similarly peaceable types, holding our ten-and-sixpennies like they

might explode at any moment. An officer and a sergeant took charge of us. We

squeezed into the back of a large, canvas-covered ghari and motored south. From

our glum expressions one might imagine we were off to the front. Quitting the

tarmac we entered the bush, dust enclosing us. Morale was low. When we stopped

and alighted we were formed into a two-line squad and marched off down a narrow

track that eventually gave way to open rocky terrain with the sea arcing beyond.

We were high up, where the views were spectacular, eventually reaching the cliff

edge. We had been on foot for about a half hour. There were ragged posts placed

in a row spaced six feet or so apart. Cardboard targets the shape and size of

a human body had been brought and they were now fastened, one to each of the

tilting posts. Our bullets, if fired at the targets with a level trajectory,

would end up going over the cliff and into the sea. There were no boats to be

seen below.

As

a consequence, one sunny morning Jack and I found ourselves in Akrotiri booking

out Stens, one each this time. We were in the company of clerks, cooks, technicians

and other similarly peaceable types, holding our ten-and-sixpennies like they

might explode at any moment. An officer and a sergeant took charge of us. We

squeezed into the back of a large, canvas-covered ghari and motored south. From

our glum expressions one might imagine we were off to the front. Quitting the

tarmac we entered the bush, dust enclosing us. Morale was low. When we stopped

and alighted we were formed into a two-line squad and marched off down a narrow

track that eventually gave way to open rocky terrain with the sea arcing beyond.

We were high up, where the views were spectacular, eventually reaching the cliff

edge. We had been on foot for about a half hour. There were ragged posts placed

in a row spaced six feet or so apart. Cardboard targets the shape and size of

a human body had been brought and they were now fastened, one to each of the

tilting posts. Our bullets, if fired at the targets with a level trajectory,

would end up going over the cliff and into the sea. There were no boats to be

seen below.