Royal Corps of Signals.

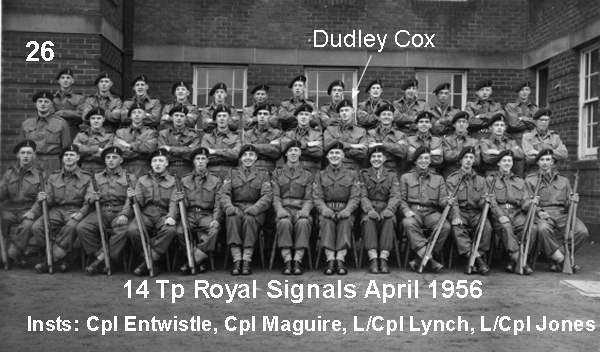

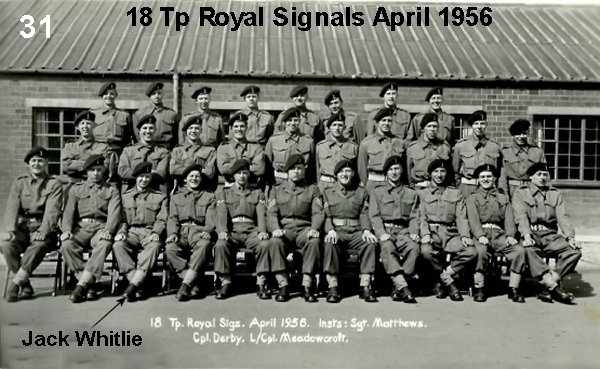

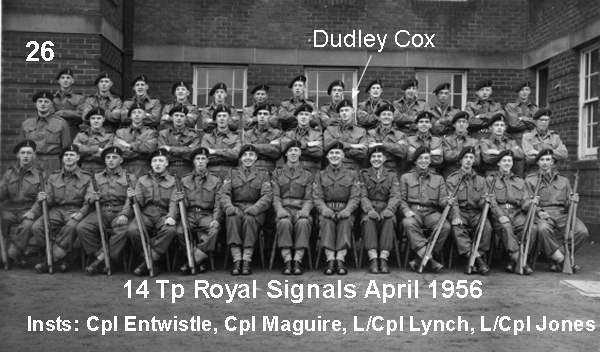

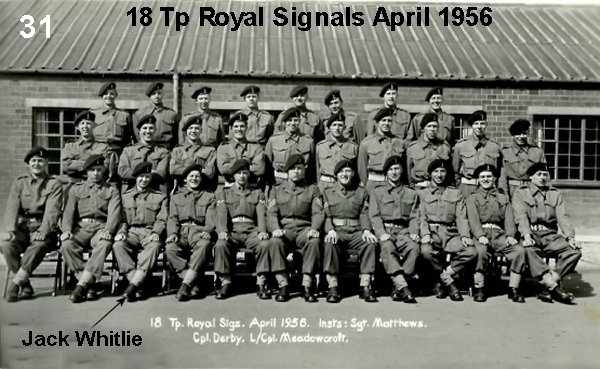

Dud's

Army

Chapter 2

Drill

Our room provided sleeping quarters to perhaps eighteen of us; I do not perfectly remember. It seems that way for on day two when we were shouted and harangued into a group outside in the roadway, self-consciously dressed in shapeless, ill-fitting fatigues, we made up a rag-tag unit of six across and three deep, a squad. We wore yesterday's issue of ugly, ill-fitting and hated black boots, my Italian slip-ons a delicate memory. We stood clumping about in our new footwear like first-day farm boys. Up and down the roadways bordering the square, squads of thistle-headed recruits were about to begin army drill.

The first time we were made to stand to attention, heads up, eyes front, shoulders back, arms stiff at the sides, fists lightly balled, thumbs facing forward and lying parallel to one's vertical trouser seams, the whole business struck me as so idiotic it was all I could do to prevent myself from falling to the ground in convulsive, manic laughter. I kept thinking that if my mother could see me, she'd break up too. But sadly, it was no laughing matter. Like colts from the paddock we were there to be broken in to the ways of our new, two-legged masters. And masters they were. Any hint of a smirk from a recruit and the drill corporal was in his face, roaring obscenities in an eye-popping, saliva-scattering tirade that rapidly metamorphosed the smirk into alarm and from there to ill-concealed terror.

They begin by teaching one to come to attention, and to stand at ease, or in plain English, how to transition from standing-still to still-standing-still. In order to do this in the form of Army drill one begins by first flinging one's knee half way up to one's chin and then, with the same leg and after the manner of Rumpelstiltskin, stamping one’s boot down to the ground. But when I did it I always raked my boot down my inside ankle. They became bloody messes. But blood was expected:

"Yew are to smash yor' feet so 'ard into the grahnd, I'll see BLUDD come spahtin' 'aht o' the bleedin’ lace'-oles. Nah, let's get it tewgether: squaaaaddu, ahhteeeeen -wait for it, wait for it you bloody,'orrible nig-nogs, WAIT for the bloody ordah, SHAAN! That was 'ORRIBLE! STANDAAAAHT EYSS!!!!"

It took us several hours to even begin to learn these postures and pronunciations for our separate selves, and then more time to achieve even a ragged synchronisation with our squad members. We were introduced to the method of turning ninety degrees to either the left or the right. The turn, on pavement, required a fractional sort of backwards hop of the leading leg once the angle had been negotiated, followed by the usual ankle-smashing delivery of the follow-up leg and boot. Then followed a leg-twisting about-turn, where the angle of circumlocution was increased to one hundred and eighty degrees. We were brought close to despair by the silliness of it but on and on it went, the indefatigable drill corporals taking it in turns to hoarsely scream their orders and subsequently jibe, jeer, scoff and sneer at our inept responses. The supply of scurrilous obscenities directed at us and our family members was inexhaustible.

All of this we endured for some days before one step of actual marching was ordered. Of course no sooner had we been ordered forward than we would then have to learn how to come to a halt, how to wheel left or right, how to about turn, how to mark time, unfortunate expression, and how to change step. This last proved an impossibility for a couple of unfortunates who were unceremoniously plucked from the squad and forced to demonstrate before the rest of us. Cruelly, we laughed at them.

Then came the rifles - bolt action 303's left over from the last war, or maybe even from the one before. We had to learn how to fling these about our bodies without knocking each other about and then fasten a bayonet to the end and repeat the process. I remember being disgusted with the bayonet. It was no more than a sharpened piece of five sixteenths round steel somewhat larger than that found on the back of a boy scouts knife uncles told us were useful for digging stones out of horses' hooves. I had expected a blade with grooves down the side for letting the air in and blood out. But the danger from the rifle came each time I performed the order-arms directive, by skinning my left collar bone and bruising my left breast muscle, recently nurtured into vague existence by a series of Charles Atlas dynamic tension exercises. I hated that rifle, and my mood darkened each time we unchained them from the wall.

I actually fired my gun a couple of times, missing the target but hitting the wooden signal stick they were waving to indicate a miss. I explained I much preferred a moving target but they were not impressed. Taking my turn in the butts, I learned at first hand what it is to come under fire. As the live rounds thrummed by not more than a couple of feet overhead and us crouched below the targets and well protected by the concrete at our backs, to my fevered imagination each bullet made as much commotion forcing itself through the air about me as if a double-decker bus had bodily passed over at the same terrifying speed. I was horrified at the potential violence, pain and disfigurement such a missile offered to the human body.

I failed the shooting exercises but felt no shame. I tried really hard to get the drill right. Possibly my position as right squad marker generated the necessary sense of purpose. Or maybe it was because my favourite style of music was traditional jazz, much of it written for the march. Most likely I learned the drill because that was the least line of resistance and the alternative unknown. There were rumours going around about the form “jankers” took, all of them worth avoiding.

. ![]()