Royal Corps of Signals

Dud's

Army.

Chapter

20

And That Was That

I looked forward to Christmas not only for its own sake but because once the year- end’s festivities were done with, the following three months seemed always to pass like wildfire. Those three months now represented all that remained of my military life.

Christmas in Bath typically involved the Works Party, a Ken Mackintosh dance at the Pavilion and the odd private party. At home in Bathford we would hang up stockings, exclaim at presents, eat a Christmas dinner, play Snakes-and-Ladders and loaf around cracking jokes and walnuts. Good humour prevailed with no stronger stimulus than a glass of port and a sense of how special the day was. In other words, being Welsh, our Christmas went along pretty much the way Dylan Thomas described his time of it. Sometimes Uncle Albert and Auntie Joyce from Wales would be with us. My mother made a special joy out of Christmas.

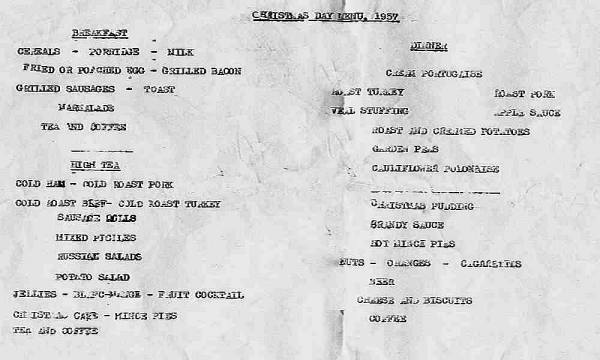

At Cape Gata we would not hang stockings and loafing around was nothing new but the sumptuous dinner we could expect. Albert The Lone Army Cook guaranteed it. One celebration we did indulge in was a camp soccer game played in pyjamas, pitting the Scots against whoever was left over, politely called “England” rather than the optional “Sassenachs.” An ordinary soccer game would have been a no-contest in favour of Scotland so we just competed at being silly, where the England team had a huge advantage, the current government continuing to provide unlimited examples. Considering the behaviour of the English at Culloden one could only admire the restraint the Scots brought to this contest.

Christmas

dinner was indeed sumptuous, and in a spotlessly clean, fly-free, dining hall,

too. Of course our Army contingent was invited to the feast, our mixed-services

Hermits group hanging out together at one end of the table. We were dressed

in our best uniforms in honour of the day. There may have been some drinking

in the NAAFI following the meal but it always came off at 280 SU without the

typical rowdiness of an Army or Navy crowd. One supposes that since these two

latter services had such an age-old tradition of raising Cain each time they

raised a glass, all subsequent recruits felt duty-bound to keep the mayhem going.

The RAF were not so lumbered with hoary traditions.

This

was the second Christmas for Jack and me at Cape Gata and had it not been for

the soon-to-come demobilisation we might have moped around a bit. One setback

we shared was the loss of our kayaks, swept away by an unusually violent storm.

I had promised my boat to one of the RAF technicians so there was nothing for

it but to get stuck in and fashion a third. I built it for him, made-to-measure,

in short order, the business helping the time to pass. My twenty-third birthday

came and went virtually unnoticed.

The General Emergency was resumed and the killing started again.

By way of a change the terrorists blew up a hanger at Akrotiri damaging the

jet fighter planes within. We heard the explosion and saw the plume of black

smoke going up. It was around this time some of the RAF radar operators detected

a visit by what might only be described as a pair of UFO’s, crossing the

night sky at a speed later estimated to be two thousand miles per hour. The

sighting was reported in to Nicosia and jets were scrambled but returned to

base with no contact reported. This came as no surprise since the Hunter pilots

used to complain about how difficult it was while out on combat exercises to

intercept their own Canberra bombers.

When the call did come for Jack and me to pack up and leave Cyprus I felt numb. I wanted to go as crazy with joy as Corporal Hodgeson had on receipt of his first pen-pal letter but that form of celebration would not have felt right. Cape Gata and its people had been home to us for sixteen months, and a good home at that. Rarely had it been institutional, quite the opposite in fact. And there had been ample opportunity to live a huge slice of my life after my own fashioning, probably more opportunity there than civilian life had hitherto offered, dominated as those two decades had been by the character and peregrinations of my parents. Until reaching one’s majority one has, after all, been subject to many forms of press-ganging. The apparent freedoms of civilian life would continue to exact their own form of paybacks I was to discover, more profound and demanding than any the Army had ever asked of me.

But the world was fiercely beckoning and by now one was trained to follow orders. Jack and I packed our kitbags. The “CYPRUS” we had so jauntily daubed on them was now as marked-up and faded an inscription as one finds on an ancient headstone.

We flew home and that was that.

The End

Addendum

But He's Not A Soldier

I know a youth who is, forsooth,

A very pretty little boy,

But he’s not a soldier ’cos he’s never been to war

And his gun is only a toy.

For your country would you fight, if a Russian came in sight?

Now give me your answer do.

I don’t know about the Queen, whom I never yet have seen,

But I’m sure that I’d fight for you.

Cradle song, Crimean war.

. ![]()