Royal Corps

of Signals

Dud's

Army.

Chapter

10

Inventions

Billy Butlin, the holiday camp mogul, was a bugler in the first

world war and a much-admired, enterprising spiv in the second. The construction

of one of his early camps at Filey, for example, was actually completed for

him by the Army who then built him two more, at Ayr and Pwlheli, handing them

over to Billy at war’s end. In my mind, the Army and Billy go hand in

hand. Auntie Rose, youngest and jolliest of my twelve aunties, was the only

one of our family to have gone to Butlin’s and from the memory of the

pictures she showed me I had cause to suppose, on first coming to our camp,

that I was at Pwlheli. In essence, 280 SU resembled a Butlin’s camp and

had Mr Butlin seen it I’m sure he would have approved the set-up, especially

as the camp occupants were able to amuse themselves without the harrying of

Redcoats or cues from loudspeakers on poles.

The place was satisfying to Jack and myself, most likely due

to the lack of bull. There seemed to be an unwritten standing order forbidding

it at Cape Gata. And, to further our delight, the Army could not officially

intrude or impose on RAF camp management. With such a political shield our Royal

Signals contingent and Albert of the Catering Corp remained largely insulated

from the slings and arrows of the more outrageous militarists. By any standard

we were on a good number. We were treated like honoured guests by a civilised

host.

Within weeks of arriving at 280 SU we had the business of being

there figured out. The camp, surrounded on three sides by bush, lay close to

a rocky sea shore but otherwise miles from anywhere. We were enclosed by barbed

wire and patrolled at night by armed RAF personnel. Personal excursions were

limited to either the water’s edge for swimming or a hike to the airfield

base at Akrotiri for pay. Fresh water arrived each day in a ghari. The nearest

town, Limassol, glimpsed across the bay to the north east, was declared out

of bounds by a situation we referred to as the General Emergency. We were on

active service, the kind they mint medals for. We could be shot at but it would

have to be a long one. We received a generous allowance of free time. And the

sun shone.

In camp one lived in a quarter of a four-cornered tent, the

other three sectors similarly occupied, two army and one RAF in my case. Jack’s

tent, across the way, was all army. So one had a place to hang one’s hat,

a home and nice neighbours. One had a job, which for us Radio Relay technicians

was cushy, providing us as much time off duty as on, an unheard of arrangement

back home. Food was good although the flies wanting a share of it were bad.

The odd luxury items like cigarettes, beer and pop were cheaply for sale in

the NAAFI managed by a stout Turkish gent of genial disposition. In the middle

of the tent lines stood a concrete-floored, galvanised iron enclosure with dribbling

taps poised above a tin trough we used for washing: selves and smalls. There

was a camp laundry service for sheets and pyjamas. The typically foreshortened-doors-and-walls,

see-your-neighbours’-boots type of row-toilets were at the north edge

of camp smelling to high heaven and not a place in which to comfortably linger.

Up to this point the army had provided me small scope for my

compulsive habit of inventiveness. True, in 4 TR I had contrived to lay an electric

cable, terminated with a pair of split, brass, female receptacles, secured within

a crack running the length of a forty-five degree wooden, ceiling-to-wall, support

beam. The far end of the cable connected to a live junction box in the loft

of our barrack hut. This facility, entirely invisible, allowed me to plug my

electric razor into the innocuous crack in the wooden beam above and shave while

laying in bed, a worthy and technologically advanced alternative to my open-

razor performances at 1 TR. The Stalag 17 inspired trickery of it gave me much

pleasure, especially when talking later in Cyprus with a new arrival from 4

TR, he assuring me my cracked-beam socket was, when he left there, still alive

and kicking.

But better prospects now offered. With all of the free time

at hand, and the famous wine-dark sea on our doorstep, I figured on building

a boat of some kind. I was not without experience. At fourteen I had cobbled

together a raft beside the coal-black waters of the River Taff. But as soon

as I got it into the river it had floated away. I could not swim then so it

carried on downstream from its launching at the Ynys Bridge to break up an hour

later on Radyr Weir. Two years on I was quietly gathering material at my workplace

for a second try, on the Avon at Bath this time, when a big storm came and blew

down all of the eight metal drums I’d readied, painted with anti-rust

and stored on the factory roof. When they came rumbling down over the corrugated

iron panels and landed below it was with a noise like thunder, causing blokes

on the shop floor to duck and the boss to run from his office. The drums were

confiscated and I gave up on the idea after that, my resources proving too slender.

Besides, not one of my friends was the least bit interested in coming in with

me on it, not even Terry. It did give me pause that my enterprises were so singular

but it did not stop me.

I

decided on a two-man kayak although I had merely a vague sense of such a vessel’s

design. I did remember from books that the Eskimo tied and waterproofed themselves

in, flipping themselves upright if they overturned. I decided against this feature

because of my horror of panicking and drowning upside-down. Not learning to

swim until eighteen I was still wary of the water. It was for this same reason

I could never dive into the blow-hole we discovered in a rocky shelf along the

coast, and swim the twenty feet out from under its projection to come up in

the open sea. Fred, a Signals lineman, demonstrated the technique but I could

never muster the courage. Fred swam like a seal, and I like someone who’d

rather be on land.

I

decided on a two-man kayak although I had merely a vague sense of such a vessel’s

design. I did remember from books that the Eskimo tied and waterproofed themselves

in, flipping themselves upright if they overturned. I decided against this feature

because of my horror of panicking and drowning upside-down. Not learning to

swim until eighteen I was still wary of the water. It was for this same reason

I could never dive into the blow-hole we discovered in a rocky shelf along the

coast, and swim the twenty feet out from under its projection to come up in

the open sea. Fred, a Signals lineman, demonstrated the technique but I could

never muster the courage. Fred swam like a seal, and I like someone who’d

rather be on land.

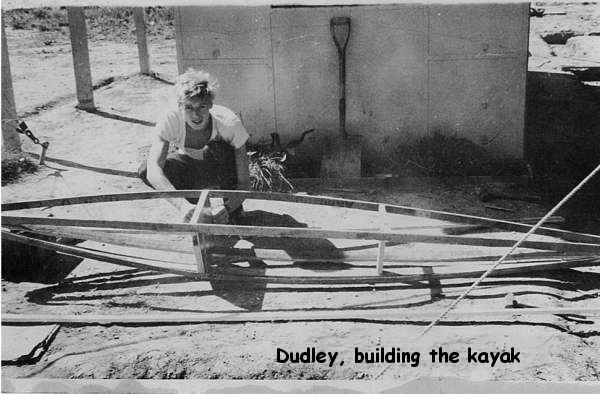

Materials and tools for this boat-building venture had to be

scrounged from around the camp. The design, therefore, would be predicated by

what came to hand. Looking for clues about kayaks in Nutall’s, I read

it was made of “a skin cover over a light framework,“ as was a coracle,

or a man, for that matter. Those touted lexicographers! But I had a picture

in my head that would serve. And in disguised forms we had the necessary stuff:

canvas, wood and paint. From wood I could make a light framework and for skins

use abandoned tent fly-sheets. The paint would waterproof the canvas. We had

a saw and a hammer. Nails one could pull out from here and there. Screws would

have been better but there was no drill, drill-bits, or screws. There were no

electric tools.

Canvas was easy to get hold of, and wood came from the piles

of packing case sections laying about, many of which measured ten to twelve

feet in length and five to six feet in height. They were made up like farm gates

assembled from wooden strips rough-sawed three inches wide and three quarters

of an inch thick. The wood itself was probably fir or spruce - certainly a softwood.

Only the odd piece had too-big-of knots in it. The RAF’s intention for

this lumber was to provide for the making of wooden tent-walls, although the

programme was a please-yourself sort of arrangement the typically enlightened,

non-Army type of common sense prevailing at 280 SU. While the RAF were making

up their minds when to get started, the Army relieved them of one kayak’s

worth of lumber.

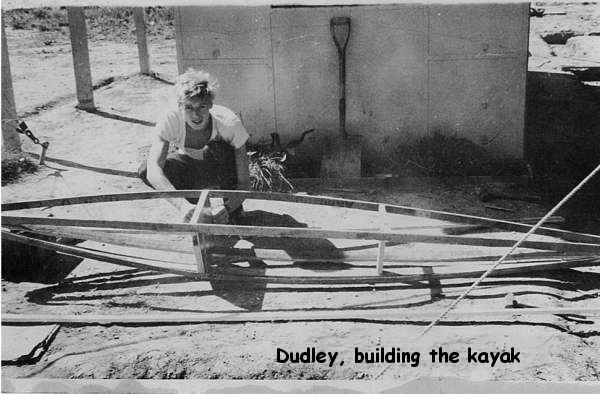

I dismantled a couple of the larger sections, easing them apart

gently to salvage all of the nails. The best looking pieces I cut lengthways

into two, making thereby pairs of matched stringers. Once cut my stringers bent

like bows. I planned to take advantage of their natural curves, so being cut

from the same cloth, so to speak, ensured the curves of each pair ran complementary

to each other. I nailed them to each of the horseshoe-shaped bulkheads, set

apart amidships to provide for two cockpits and serve as backrests to the paddlers

- Jack and me. The transom was, in shape, a miniature version of the bulkheads

and to it all stringers running aft were then bent and nailed. I had no workbench

or even a table, so I worked off a flat bit of ground in the dusty shade provided

by our equipment hut.

With amidships and stern secured I was now faced with my stringers

projecting from the forward bulkhead some eight feet. I tied a rope around them

and applied a tightening all around like a tourniquet. With the ends just touching

and striving for an upward and forward sweep of the stringers I could pencil

on them the rough tapers needed to bring them together in a bit of a pointed

edge. I either sawed or chiselled these tapers. When I had it right I nailed

the ends together. This required some care because if a stringer end split I’d

get what the English prime minister was getting around that time: a serious

setback, although unlike his situation I could begin again.

Why the true lines of a ship are so satisfactory to observe

is surely due to those same lines already existing somewhere in nature. The

joy derived by man from this observance stems from recognising nature’s

forms repeated in his creation. It is akin to seeing a rightness and is doubtless

the same joy that makes a dog wag his tail. So with the hull built to outline

form and happily beheld - with one or the other eye closed, one wants nothing

more then than to get on with the finish of it and put it to the test.

With the help of Albert the Army cook I was delivered a tea

chest, which taken apart provided five square panels of quarter inch plywood

and a pile of one-inch, flat-headed nails. Pieces of the this ply were tacked

into the sitting positions, bending easily to the curve of the boat below the

waterline and adding transverse strength to the sections forward of the bulkheads.

The sharp outer edges of the stringers were softened with the chisel before

Jack and I wrapped the canvas around the frame and tacked it with our tea chest

nails to the upper stringers. The bow was a challenge once the top panel was

on as we had canvas ends sticking out like the head of a leek. After some serious

swearing and judicious scissoring we rolled what was remaining together and

nailed the roll in tight. Everything was painted oil green. What with the padding

of the seats and making two pairs of paddles the whole job from concept to sea-ready

was completed, in three weeks. It was surprisingly heavy but we carried it out

of camp, along the path and down the cliff.

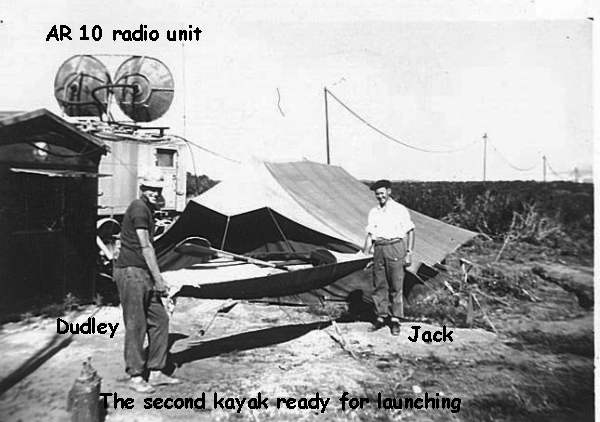

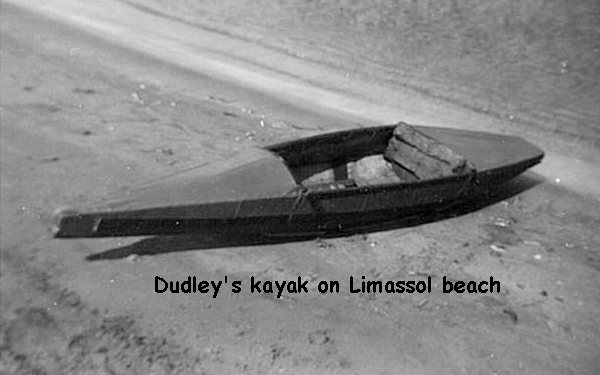

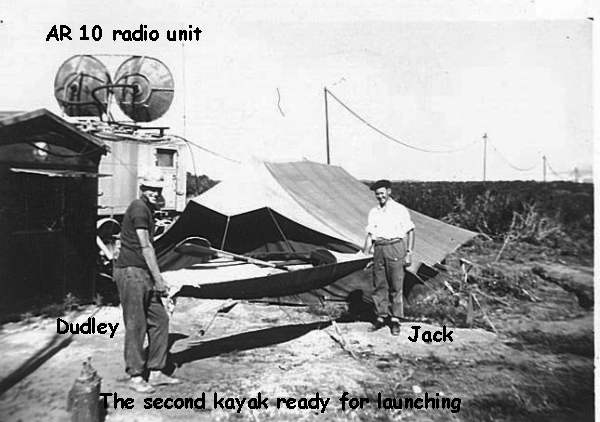

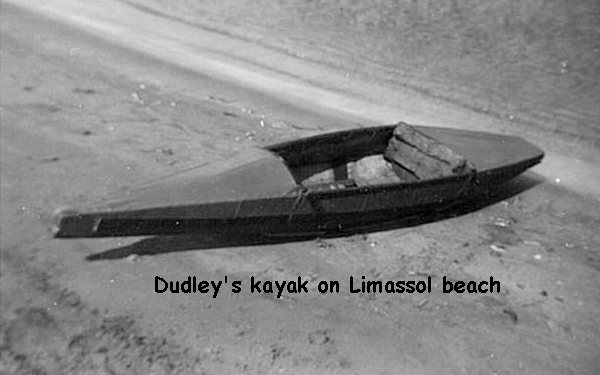

It

floated grand and did not leak even a spoonful. But the kayak I’d made

would not carry two persons. With Jack seated forward and me behind we were

way too low in the water. I got out and Jack went off on his own, as consumed

an Army paddler as any Army driver. He was flying. I’ve never seen him

so pleased with anything. The kayak now rode beautifully and Jack was perfectly

placed in the forward cockpit, just aft of centre. She was a beauty, that little

ship, longer than you might at first think she needed to be, like a tall person,

maybe. And Jack did not want to get out of her. He was going around the little

bay we swam in like a marina porpoise. “She’s your’s Jack”

I said, and that was that. I’d build another one. I already knew what

modifications I planned to make. I couldn’t wait to get back up the cliff

to camp to go sawing.

It

floated grand and did not leak even a spoonful. But the kayak I’d made

would not carry two persons. With Jack seated forward and me behind we were

way too low in the water. I got out and Jack went off on his own, as consumed

an Army paddler as any Army driver. He was flying. I’ve never seen him

so pleased with anything. The kayak now rode beautifully and Jack was perfectly

placed in the forward cockpit, just aft of centre. She was a beauty, that little

ship, longer than you might at first think she needed to be, like a tall person,

maybe. And Jack did not want to get out of her. He was going around the little

bay we swam in like a marina porpoise. “She’s your’s Jack”

I said, and that was that. I’d build another one. I already knew what

modifications I planned to make. I couldn’t wait to get back up the cliff

to camp to go sawing.

One odd thing I was finding out about myself was that not only

did I love building things but I frequently loved the building more than I loved

the use of what I‘d built. So far as the kayaks were concerned it came

out about equal. And the particular joy derived from fashioning these kayaks

was due to the improvisational aspects of the design and having only the very

minimum of tools and materials to hand. The process was gratifyingly simplified.

By a happy accident of personal fortune, and full thanks to the Army, I found

myself following in Robinson Crusoe’s footsteps.

Chapter

11

Home

.

I

decided on a two-man kayak although I had merely a vague sense of such a vessel’s

design. I did remember from books that the Eskimo tied and waterproofed themselves

in, flipping themselves upright if they overturned. I decided against this feature

because of my horror of panicking and drowning upside-down. Not learning to

swim until eighteen I was still wary of the water. It was for this same reason

I could never dive into the blow-hole we discovered in a rocky shelf along the

coast, and swim the twenty feet out from under its projection to come up in

the open sea. Fred, a Signals lineman, demonstrated the technique but I could

never muster the courage. Fred swam like a seal, and I like someone who’d

rather be on land.

I

decided on a two-man kayak although I had merely a vague sense of such a vessel’s

design. I did remember from books that the Eskimo tied and waterproofed themselves

in, flipping themselves upright if they overturned. I decided against this feature

because of my horror of panicking and drowning upside-down. Not learning to

swim until eighteen I was still wary of the water. It was for this same reason

I could never dive into the blow-hole we discovered in a rocky shelf along the

coast, and swim the twenty feet out from under its projection to come up in

the open sea. Fred, a Signals lineman, demonstrated the technique but I could

never muster the courage. Fred swam like a seal, and I like someone who’d

rather be on land.

It

floated grand and did not leak even a spoonful. But the kayak I’d made

would not carry two persons. With Jack seated forward and me behind we were

way too low in the water. I got out and Jack went off on his own, as consumed

an Army paddler as any Army driver. He was flying. I’ve never seen him

so pleased with anything. The kayak now rode beautifully and Jack was perfectly

placed in the forward cockpit, just aft of centre. She was a beauty, that little

ship, longer than you might at first think she needed to be, like a tall person,

maybe. And Jack did not want to get out of her. He was going around the little

bay we swam in like a marina porpoise. “She’s your’s Jack”

I said, and that was that. I’d build another one. I already knew what

modifications I planned to make. I couldn’t wait to get back up the cliff

to camp to go sawing.

It

floated grand and did not leak even a spoonful. But the kayak I’d made

would not carry two persons. With Jack seated forward and me behind we were

way too low in the water. I got out and Jack went off on his own, as consumed

an Army paddler as any Army driver. He was flying. I’ve never seen him

so pleased with anything. The kayak now rode beautifully and Jack was perfectly

placed in the forward cockpit, just aft of centre. She was a beauty, that little

ship, longer than you might at first think she needed to be, like a tall person,

maybe. And Jack did not want to get out of her. He was going around the little

bay we swam in like a marina porpoise. “She’s your’s Jack”

I said, and that was that. I’d build another one. I already knew what

modifications I planned to make. I couldn’t wait to get back up the cliff

to camp to go sawing.