Royal Corps

of Signals

Dud's

Army

Chapter

5

1 Training Regiment

1

TR, as the First Training Regiment Royal Signals was generally referred to,

introduced me to the world as it was understood by a motley cross-section of

educated young men, a company startlingly new to me. Once in residence there

I soon came to recognise my ignorance and again suffered the shock of a savagely

widened horizon. But whereas Basic Training had introduced me to terror, 1TR

offered me both wonder and inspiration. The place became my alma mater, my nourishing

mother. And being April, going on May, spring was in the air, a good time for

beginnings of any sort.

1

TR, as the First Training Regiment Royal Signals was generally referred to,

introduced me to the world as it was understood by a motley cross-section of

educated young men, a company startlingly new to me. Once in residence there

I soon came to recognise my ignorance and again suffered the shock of a savagely

widened horizon. But whereas Basic Training had introduced me to terror, 1TR

offered me both wonder and inspiration. The place became my alma mater, my nourishing

mother. And being April, going on May, spring was in the air, a good time for

beginnings of any sort.

The camp was arrived at by means of a downhill road that levelled

off into a sort of uneven plateau. There was a guard house, a modest drill-square

and shed, an H.Q., a cookhouse and a series of creosoted wooden barrack huts

straggled about, some to live in and others for classes. A network of tarred

pathways linked all together, the edges of the camp petering out into untended

grass and bush, too lumpy and wild to make any kind of area for football or

cricket.

I was assigned a barrack hut along with Gerry, a fellow nig-nog

coming to Catterick from working in a garage in Ipswich. We were somewhat overawed

by the resident company. We’d hang out in silence, for example, as an argument

ranged about the room regarding the legitimacy of charges brought against an

ancient Greek called Socrates for corrupting young men. I whispered to Gerry,

dozing horizontally in his bed alongside, questioning what we were doing here

with this lot. They‘re all la-de-dah, posh, I said. It was difficult to know

what they were going on about half the time. We were garage and factory, shop

floor blokes. Gerry remarked it was all to do with that test we‘d taken from

the intelligence joker. It was an IQ test, he said. We were bright, that’s all,

ignorant but bright.

Pleased with this reason for my being at 1 TR, I cast about

for some form of mark I might make, a stake to my claim of legitimate inclusion,

a metaphorical lifting of the hind leg, so to speak. I had read in Gilbert Harding‘s

autobiography that when in exalted company one requires an identifying feature,

something to single one out and set one up. He had settled for wearing a long

black cloak, poncing about the Cambridge colleges like an advertisement for

Sandeman’s Port. For my part I took to shaving with an ancient bone-handled,

open razor, an antique cut-throat. My Sweeny Todd early-morning display, a slick-wristed

sharpening on a leather strop followed by a flashing, blood-free shave, proved

entirely satisfying, incurring zero competition from my safety-razoring peers.

To be honest I was so fair and fresh-faced I only needed one shave a week but

I’d play the scene each morning just the same.

As an added feature I began to style my hair like a youthful

Caesar, which was all very well but did call for self-barbering - one could not trust the local establishments. I bought proper scissors for the purpose

and knew how to sharpen them, too. In spite of my sanity being questioned by

one of our more conservative corporals, he still clinging to the much-despised

side parting, my efforts couldn't have looked too bad as several blokes approached

me for haircuts, which I blithely provided. I'd learned to cut hair from watching

my mother trim my sisters' hair, and of course I had studied the work of my

own barber.

could not trust the local establishments. I bought proper scissors for the purpose

and knew how to sharpen them, too. In spite of my sanity being questioned by

one of our more conservative corporals, he still clinging to the much-despised

side parting, my efforts couldn't have looked too bad as several blokes approached

me for haircuts, which I blithely provided. I'd learned to cut hair from watching

my mother trim my sisters' hair, and of course I had studied the work of my

own barber.

The move to a technical training unit did not stop the army’s

determination to make soldiers out of us. Right off we were cautioned to read

orders, which meant daily visits to the administration building to read the

camp notice board. There were displayed the disagreeable tasks they planned

for us along with a corresponding list of names to whom the chores applied.

Being absent from an assigned duty could not be legitimised by not reading the

order since not reading orders was a crime. If you did not read orders and you

were up for a job you were disobeying orders in duplicate i.e. failure to obey

in general and failure to obey in particular, two crimes for which one was brought

up on two charges and penalised two times. For this one either lost pay, got

jankers or both, whichever hurt the most. I cannot report on jankers as neither

I nor my friends got a sampling. In our still-civilian minds, jankers was tantamount

to going to prison.

In keeping with the general principle that the military is

a world unto its own, the camp services, except in the case of electricity,

water and sewage, were self-managed. To feed us, for example, we had cooks.

These were Army cooks, the kind who do not peel potatoes or clean pans. Spud

bashing found one in an ugly concrete room wherein stood a pyramid of potatoes,

chest high and spreading out close to the walls where one sat on a stool, the

outskirts of this cartload tumbled about one‘s boots. There would be four

or five of us grouped around this mountain of misery, armed with knives. As

each spud got bashed it was tossed into the water-brimming metal sink in the

corner. Some blokes cannot peel spuds much less take the eyes out or recognise

signs of rot within. As a consequence many of our potatoes ended up resembling

dodecahedrons, suffering a chopping rather than a skinning. The black lumps

one found in the mashed spuds on one’s plate were the cooked innards of

our missed rotten ones. It’s my guess that the pigs who fed off 1 TR's

peelings fattened faster than average.

A worse job than peeling spuds was cleaning the pans in which

our food was cooked. After some hours one’s hands grew red and sore from the

scouring with spiralled-copper pads. The wash water rapidly darkened and became

so greasy and smelly one felt nauseous at one‘s wash station. In actuality the

pans were never cleaned of all that was baked into them and so whatever grub

was cooked in them inevitably tasted of dirty pan.

We had our own fire department, the hose wound around the axle

housing of a two-wheeled cart. This latter had a pair of shafts projecting from

it and was originally designed to provide seating for driver and passenger and

be drawn by a horse. It took six of us nig-nogs to do what the horse did, although

the hose did not outweigh two persons by a long shot. When first assigned to

the duty one was shown how to connect the hose-end to a hydrant and how to squirt

water out of the other end. Two men were assigned to the nozzle as in spite

of a memorised drill of shouted warnings and shouted back acknowledgements,

the arrival of the water came with a violent, hose-stiffening rush. A daydreaming

firefighter, especially a nig-nog techie, would be knocked off his feet by the

impact, along with anyone else in range of the now-flogging, bronze-ended, spouting

terminator. Due to the high number of creosoted wooden huts, they were always

staging fire alarms, twice a week at least, each time requiring the entire camp

population to muster on the square. The twelve-legged, two-wheeled, twin-shafted

fire-engine inevitably showed up last but was always given a rugby cheer by

the men on the square. Say what you like but 1 TR was a cheerful place.

Eight months before I was called up the I.R.A. robbed an artillery

barracks in southern England. They took the contents of its armoury -an extensive

inventory of Stens, Brens, Lee Enfields, pistols, explosives and ammunition.

The entire barracks population of six hundred English soldiers slept through

the raid. 1 TR had nothing to offer the Irish’s need for weapons but knowledge

of that Berkshire caper kept all of us nig-nogs up to the mark. Of the four

nations purported to be British, the Irish were the most unpredictable, volatile

and talented.

A guard duty saw six to eight of us Signalmen, for that was

what we were now called, protecting the 1 TR camp for a stint of twenty-four

hours. By means of a brief but formal ceremony we reported as a squad to the

guard room in full kit around four o’clock in the afternoon. Thereafter, in

two hour shifts, a pair of us armed with baseball bats combed the camp to its

untended edges looking for rascals. There was no formal instruction on the use

of this American club, the Army relying on our Neanderthal origins, but as a

weapon we all agreed it was superior to the cricket bat for bashing invaders.

After two hours of coursing our hutments we would return to the guard house,

liberating the next pair of baseball players to take up the cudgels. We could

now rest in the guardhouse for four hours until it became time to go out and

guard the camp again. This pattern of two hours on, four hours off repeated

through the night.

During the following day’s daylight hours we switched

to a Buckingham Palace routine, taking it in turns to stand on guard, singly,

outside of the guard house. We paraded there with a 303 Lee Enfield - no bullets

in it but with the much-despised, stone-digger bayonet attached to its muzzle.

One was granted certain freedoms of movement and posture while outside maintaining

this duty but the commissioned officers who passed by were to be saluted. A

captain-and-under received a common slap to the butt, of the rifle of course,

held at the slope-arms position, while a major-and-up got the full-Monty: a

one-two-three positions, present-arms salute, requiring a knee to the chin and

Rumpelstiltskin stamp along with a kind of praying gesture of the free hand

pressed against the rifle to bring it to completion. Some officers went by on

bicycles so one needed to be alert to read their shoulder epaulettes correctly,

but they were never very speedy. If one mistook the Regimental Sergeant Major

for a commissioned officer, as some Signalmen did, the resultant vituperative

wrath that fell on them would have them shaking for the remainder of the watch.

When one grew tired of standing to attention and with no officers in sight one

could march a few paces in parallel with the guard house frontage, all movements

performed smartly and formally. Of all our extra-curricular duties, guard duty

was the most onerous.

It was at 1TR one regained the resource of and permission for

wearing civilian clothes. I soon discovered where the best Saturday dances were

held, although the first time I made the mistake of going in uniform. All the

girls knew a nig-nog when they saw one, the absence of any vestige of rank on

my sleeve working against me like a leper's bell. In civvies one was at least

accepted for a dance. These dances were in Darlington, with a last crowded bus

back to camp laid on. I could not persuade anyone to go with me for quite some

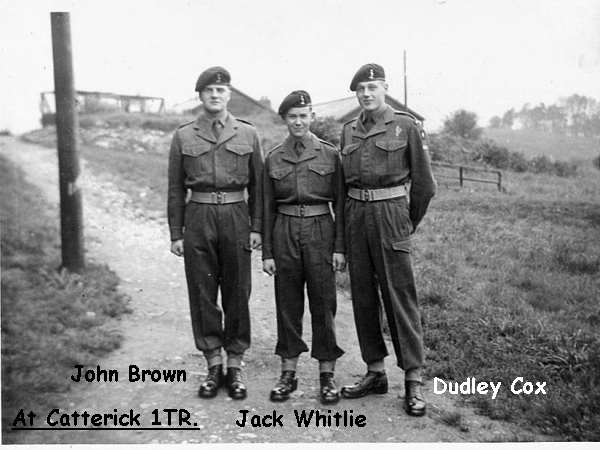

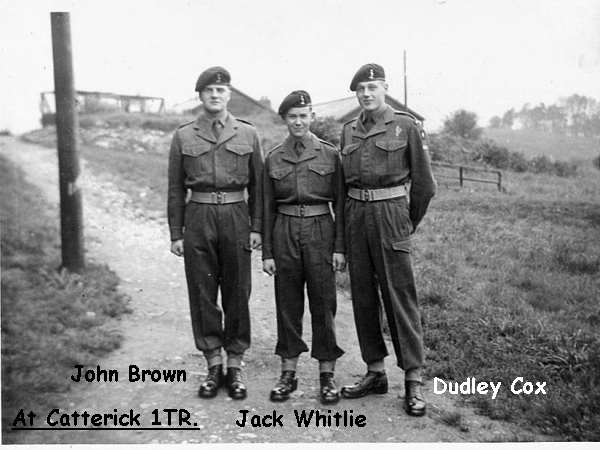

weeks, so, as usual, I went on my own. I eventually teamed up with John Brown

from Glasgow, and was glad of his company. John would tell the girls he was

either a pilot-in-training, or some such nonsense, and then a week or two later

come to me in a panic since he’d invariably forget to which girl he’d given

which biography. My closest friend, Jack, who I'd first met at the finish of

the Basic Training passing-out parade would not, try as I might to persuade

him, go dancing. Same thing with Gerry.

Nevertheless, even though Jack and I did not get quartered in

the same barrack hut, we became good friends. We would take our meals together,

except for breakfast, due to Jack never getting out of his bed until the very

last possible moment, me the opposite. But over a weekend, for example, always

in uniform, we'd go off hitch-hiking around when we had say a thirty-six hour

pass which allowed too short a time for me to get to Bath and back, or Jack

to Edinburgh. I introduced Jack to "barning," an invention of my Bath cycling

club, except we were now hitchhiking in Yorkshire instead of biking around the

West Country. One went hell-for-leather in an outward bound direction until

supper time, then diverted from travel to finding a place to sleep. usually

a barn, very occasionally with hay or straw in it. Barns, I discovered, were

not as prolific in the north as in Somerset. On one trip we ended up on the

beach at Whitby, spending the night inside a bunch of deckchairs heaped on the

sand. We crawled in from either end and did not meet up until the next morning

when we crawled out. We were both shattered. The man coming to his deckchairs

was surprised, too. That was a hard night. But there was a public Wash-and-Brush-Up

handy, staffed by an ex-army man from the First World War. Seeing us boys in

uniform we received free hot water, soap and towels.

This supportive attitude from the civilian population was to

be found wherever we wandered. Perhaps it was because the war had been over

only eleven years. Maybe Jack and I looked more like child-cadets than soldiers.

Whatever the reason, we were cheered by the general thumbs-up bonhomie. It took

the sting out of conscription.

I had not been in 1T.R. a week before seeking out a bookshop

in Richmond, a small town close to camp, where I bought a red, cloth-bound copy

of “Nuttall’s Standard Dictionary of the English Language,” the contents declared

to be “… based on the labours of the most eminent lexicographers.“ Just the

job. Before forking out my precious shillings I checked out to see if Socrates

was within, gratified to find reference to him, his mates, his unpleasant wife

Xanthippe and a few bonus remarks on Plato added for good measure. How I treasured

that book and took to reading it as some might a novel. 1 TR had already triggered

what no other authority had to that date managed: an inducement in me to learn.

At the 1T.R. receiving interview designed to decide what programme

of studies one was to follow I finally realised we were to learn radio theory.

I was asked did I prefer “Heavy” or “Light.” I had no idea what these words

meant in the radio world, so equating ‘heavy’ to ‘big’ I opted for the former.

When working back in the factory the bigger motors were the most difficult and

so garnered more status for he who worked on them. I was all for any status

going.

We attended class every day as the corporals set about teaching

us the necessary basic technology, initially common to both the Heavy and Light

courses. My four years of three-nights-a-week at Bath Tech. had essentially

provided me a good grounding in mathematics, engineering drawing and physics,

while the five years of shop work attending to electric motor windings provided

a practicum that was at least a distant cousin. So I felt confident I could

stay the course. But compared to the physical dynamism of motors and generators,

electron clouds and valve characteristics appeared to me as a pale and feeble

rider indeed. I could not whip up enthusiasm for the subject. I scraped through

the weekly tests being reluctant to swot up, partly because it was being forced

on me and partly on it not good form to be keen. Conscription was yet a bitter

pill to swallow. I was doing enough to get by, largely motivated by vanity.

I was not the only one at 1 T.R. who literally hated being press-ganged

into the Army and in fact the word ‘hate‘ became a catchword in local parlance.

We even mounted a protest march around the camp one afternoon, holding aloft

the elephant-eared stems of some giant rhubarb-like plants we found growing

around the scrubby camp-edges. This form of protest placard was copied from

the curious behaviour of some university types I’d observed at the Beaulieu

Jazz Festival. There was quite a group of us, stamping our way around the huts

chanting “hate” at the tops of our voices. What with our rhubarb umbrellas and

singularly ambiguous statement of protest we must have appeared pretty harmless.

At any rate, no-one of authority took the least bit of notice. One could not

help admiring 1 TR for such forbearance.

There were two other words bandied about at 1 TR besides ’hate’

that became part of the camp lexicon: specifically ’keen’ and ’thick.’ One did

not want to be perceived as ’keen,’ swotting up on class material, for example,

or overdoing it with the spit and polish. In fact, behaving in a military manner

except while under direct orders or in any way endorsing the ways of the Army

was anathema if one hoped to retain any vestige of self-respect. Being considered

’thick,’ on the other hand, would have meant one’s mentality was so impaired

as to place one at the same intellectual level as a regular soldier. A visual

measure of ‘thickness’ manifested as the upside-down service stripes on a regular

soldier’s tunic sleeve. These we called ’thickness stripes,’ the very sight

of which required from us national service types a thinly disguised shudder.

This was out-and-out snobbery but it helped us along.

I did go on a raid. One of our barrack hut corporals, a moustachioed,

Napoleonic type moodily serving his Elbaan exile at 1 TR following expulsion

from O.T., decided to turn the beds of a neighbouring hut upside down. The upturning

was to include the sleeping occupants. We were drilled for the manoeuvre, rehearsing

the process in our hut and with assigned beds - all huts were laid out pretty

much the same. At the appointed hour, in pitch darkness, we silently got ourselves

out of bed, dressed and lined up in combat order along the corridor. I had wondered

if we would blacken our faces or even synchronise watches, but did not ask.

I did see someone in a balaclava. Napoleon then led the way as we quietly moved

into position. At the given signal we tipped the beds, easily done by means

of grasping the long side of the mattress frame and hauling mightily upwards.

Amidst the groans and curses of the suddenly awakened sleepers we picked our

way outside and were back in our own beds as quick as a wink. It was then I

realised how incriminating charcoal on our faces would have been, had an alarm

gone off and the Red Caps called in for an everybody-by-their-beds call. But

all passed well. I fell asleep straining my ears for any sounds from the passage

outside. Being the resident nig-nogs Gerry and I were given beds closest to

the door. But we suffered no casualties and received no retaliation. It was

quickly forgotten. There came soon after the Suez Crisis.

One of the senior journeymen working alongside me in Bath, Jimmy

Quinton, had served as a Signals lineman in Ceylon and Egypt. In Egypt, as he

put it, he “… dug a lot of holes in the desert,“ but it was his Egyptian crew

who did the actual digging, and setting in of the poles. It was hot and boring

work so sitting in the shade of the vehicle with the chief whip, as the Egyptian

gang boss was apparently called, Jimmy would figure out ways to rile him. His

favourite routine was to kneel as in a praying posture and with his cupped hands

scoop the sand before him and then let it dribble through his fingers, all the

while crooning “King George’s sand. King George’s sand. King George’s sand.”

“King Farouk sand” the whip would whisper. Jimmy, raising his voice and addressing

the blue sky above, would continue sieving the sand and declaring for King George.

The whip would get progressively more agitated, eventually screaming his support

for King Farouk until all patience ran out and they would fall to wrestling,

the digging crew by this time making threatening gestures with their bars and

shovels. Jimmy, a superb athlete, assured us that he could get a headlock on

the whip inside of five seconds and easily force a half strangled “King George

sand” out of him. Once released the whip would inevitably take his cane and

his chagrin to the backs of his crew and along with a string of Arabic curses

drive them back to their work. But the sands of Egypt and her waters for that

matter began running out for both kings when Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power.

On the 26 th. of July, 1956, Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal

in retaliation for the U.S. and Britain withdrawing their promised funding of

Egypt’s Aswan Dam project. There was much outrage expressed in our barrack

hut over reneging on the promise, along with open admiration for Colonel Nasser.

I was astonished at the criticism of England. I might have hated the Army for

so unceremoniously conscripting me but libellous mutiny at a time of national

crisis was a bridge too far. I could grumble well enough but anything more overtly

critical of the British government felt instinctively wrong. I was a loyal subject

without knowing why. I listened to the arguments but kept my own counsel. Privately

I worried that Anthony Eden was not the right man to handle the flak of it all.

I reckoned we needed a Winston.

But as the year progressed there were changes in my own affairs.

By the end of summer a handful of us newer fellows were selected to transfer

to 4 TR for a pilot course of study centred around the more recently developed

frequency-modulated type of radio signalling. My closest army friend by now,

Jack Whitlie, was with me in this group.

So it was goodbye to Ken Scotland, 1 TR’s most famous P.T.I.,

goodbye to our jazz-band corporal and his double bass, the instrument either

gracing his locker top or the roof of an Austin Seven for the frequent trips

he made to the cellars of London. And where else might one find such an eccentric

Catering Corps officer as ours at 1 TR mistakenly inspecting a bunch of us in

fatigues while rehearsing our first guard duty, or, in response to Jack’s dinner

time complaint there was no meat on his plate had stoutly defended the Corps

by declaring the gravy to be “inordinately thick.” For better or for worse we

were off to 4 TR. We received a long enough leave for us all to go home.

Chapter

6

DUD'S

ARMY INDEX

PERSONAL PAGES

INDEX

Home

1

TR, as the First Training Regiment Royal Signals was generally referred to,

introduced me to the world as it was understood by a motley cross-section of

educated young men, a company startlingly new to me. Once in residence there

I soon came to recognise my ignorance and again suffered the shock of a savagely

widened horizon. But whereas Basic Training had introduced me to terror, 1TR

offered me both wonder and inspiration. The place became my alma mater, my nourishing

mother. And being April, going on May, spring was in the air, a good time for

beginnings of any sort.

1

TR, as the First Training Regiment Royal Signals was generally referred to,

introduced me to the world as it was understood by a motley cross-section of

educated young men, a company startlingly new to me. Once in residence there

I soon came to recognise my ignorance and again suffered the shock of a savagely

widened horizon. But whereas Basic Training had introduced me to terror, 1TR

offered me both wonder and inspiration. The place became my alma mater, my nourishing

mother. And being April, going on May, spring was in the air, a good time for

beginnings of any sort. could not trust the local establishments. I bought proper scissors for the purpose

and knew how to sharpen them, too. In spite of my sanity being questioned by

one of our more conservative corporals, he still clinging to the much-despised

side parting, my efforts couldn't have looked too bad as several blokes approached

me for haircuts, which I blithely provided. I'd learned to cut hair from watching

my mother trim my sisters' hair, and of course I had studied the work of my

own barber.

could not trust the local establishments. I bought proper scissors for the purpose

and knew how to sharpen them, too. In spite of my sanity being questioned by

one of our more conservative corporals, he still clinging to the much-despised

side parting, my efforts couldn't have looked too bad as several blokes approached

me for haircuts, which I blithely provided. I'd learned to cut hair from watching

my mother trim my sisters' hair, and of course I had studied the work of my

own barber.