Royal Corps of Signals

Dud's

Army.

Chapter

16

Heat

With the arrival of summer came the heat. The sun would be up around five a.m. and everything would be cooking nicely by six. I would be sitting outside the equipment hut shortly after sun-up with my bare back against the metal-clad, shed wall, idly flicking swatted flies out of the shadow and into the sunlight for the pet lizard’s breakfast. He would dart out from his home under the hut, mighty pleased with the service.

Walking

back to the tent lines going off shift at seven a.m. the trip was frequently

enlivened by a mock attack from one of Akrotiri’s Hawker Hunter fighter

jets. Sometimes he’d come at us from out of the sun, or alternatively

slide in low from the sea and just flip over the cliffs, our antennas and tent

lines at the last moment. Either way I would not hear or see him coming, his

enormous shadow so suddenly above it would cause me to cringe reflexively back

in fright. I would raise my fist to curse his departure and then almost fall

backwards as the wall of sound came crashing down. Heart beating and “panic

in one‘s breastie“ I felt as Burns’ “cowrin, timorous

beastie‘” must have felt at the sight of a grown man towering above

him. Still half asleep at this hour and thinking only of breakfast, so rude

an awakening by such a terrifying war machine was shattering. Small wonder there

are so many military attacks at dawn.

The first general reaction to summer’s arrival around camp was to roll up the canvas tent walls on all four sides, tying them in position with the stitched-on strips placed at the roof edge for that purpose. The wooden tent walls, for those who had them, stayed in position leaving a six inch gap all around allowing morning and evening breezes fair access. Praise be there were no mosquitoes. Modified thus the tent became a double-layered roof, not unlike an oblique, cant-edged, flying object, the upper shield taking the brunt of the scorching sun. I found this change to our little house strangely pleasing, my abode now appearing even more temporary than hitherto and curiously modern.

In regard to taking pleasure from changes to one’s living space I took after my mother. Of course, she could not alter our house’s roof lines but the furniture within would be completely re-arranged every six months or so, irrespective of whether the new placements proved comfortable or matched the position of the pictures which were never moved because of either the wallpaper or the paint fading underneath. When the furniture change-abouts no longer gave her pleasure or rest, she would agitate to move house. Over their married years my parents lived in four different counties, fifteen different houses, seven of them in and around Bath, six while I was in the army and one of those in Devon. I conclude thereby that in olden days, mother’s Welsh pagan ancestors were of a migratory nature. This moving about played havoc with our schooling, much of the resulting damage impossible to repair.

The

heat would beat down through the day unabated. For off-duty blokes who did not

take the waters this meant either the shade of the NAAFI tent and the comforts

of nearly-cold beer, or laying about in one’s own tent or a neighbour’s.

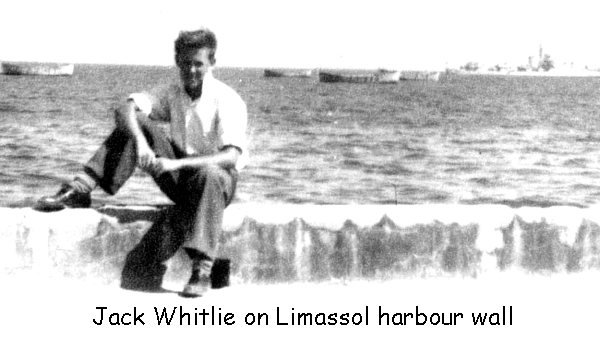

But both Jack and I were of the mad dog variety Noel Coward sings about and

braved the midday sun. Two years lost to the Army was too high a price to add

on compound interest in the shape of inertia or malaise. We did not drink beer

that much, either. One was prepared to go on a bender when the cause was great,

but such an occasion came rarely.

The

heat would beat down through the day unabated. For off-duty blokes who did not

take the waters this meant either the shade of the NAAFI tent and the comforts

of nearly-cold beer, or laying about in one’s own tent or a neighbour’s.

But both Jack and I were of the mad dog variety Noel Coward sings about and

braved the midday sun. Two years lost to the Army was too high a price to add

on compound interest in the shape of inertia or malaise. We did not drink beer

that much, either. One was prepared to go on a bender when the cause was great,

but such an occasion came rarely.

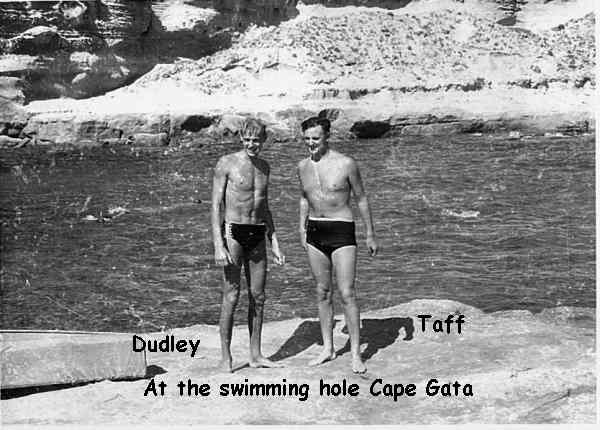

So we’d go swimming, where to escape the heat one submerged.

Under the water’s surface was safe from the sun‘ burning but pleasantly

illuminated

by his shining rays of light. And a new world materialised for me when I discovered

the swimming mask. We bought them in Limassol and their design was such that

the entire face was encapsulated by the visor. A ping pong ball served as a

valve stopper in the breathing tube. The eminent lexicographers who compiled

my Nuttall’s dictionary never encountered the word “shuftiscope,”

which is the name these swimming masks went by, testament to the British soldier’s

genius for coining delightful words way ahead of the ken of the lexi crowd.

illuminated

by his shining rays of light. And a new world materialised for me when I discovered

the swimming mask. We bought them in Limassol and their design was such that

the entire face was encapsulated by the visor. A ping pong ball served as a

valve stopper in the breathing tube. The eminent lexicographers who compiled

my Nuttall’s dictionary never encountered the word “shuftiscope,”

which is the name these swimming masks went by, testament to the British soldier’s

genius for coining delightful words way ahead of the ken of the lexi crowd.

I remember my first time using the shuftiscope, standing waist high in the clear, warm Mediterranean sea and stooping forward to take a look below. The vision thus revealed was astounding. The watery medium, hitherto a shifty and indistinct kaleidoscope perceived through one’s uncomfortably compromised eyeballs awash in salt water was now magically presented in Todd AO. I jerked my head from the water in a panic, the revelatory shock so disorienting. I took a breath and returned to the water, coasting tentatively out amongst a plethora of technicoloured marvels, joining the coloured and casual fishes to whom this watery world was just an everyday go-about. One could see to the sandy bottom, ahead and all around. One became aware of one’s progress through the gently deepening water. Fish abounded, of all colours, shapes and sizes. One could reach out to the little ones and all but touch their tails. How easily they moved. Swimming further I went over the underwater cliff, so to speak, distinctly experiencing a vertigo as I sensed rather than saw the sudden immensity of the depth of darkening water below. I came back in a hurry, my fear of heights having curiously manifested. The shuftiscope was a brilliant addition to swimming in the Med.

On the dark side, the heat of summer brought to our 280 SU camp a proliferation of blowflies, attracted to the waste food generated by the cookhouse, baking in open dustbins outside at the back until the ghari came to move them. The noise made by the flight of these insect hordes was sickening. From the dustbin area the flies expanded their spheres of influence to wherever else the food travelled, including our dining room adjacent to the cookhouse. The flies were of the bluebottle variety of the aptly named species calliphoria vomitaria, growing up to a half inch in length and hanging out in packs. On a bad day one would find one’s place at the table crawling-black with them, a spot for one’s plate attained by a vigorous sweep of the arm, causing them to burst up snarling into the air like engines in a dogfight. We had to crouch over the meal and beat off the flies with one hand. Our food was good but the ingestion of it, irrespective of taste and texture, became the sole preoccupation at meal times. This unpleasantness is the only black mark I could ascribe to Cape Gata.

I was not so aware of the flies at Paramali, there being no dining room and it almost always being very windy there. But as a result of having to carry my meal from the doorstep of the cookhouse, through the breezes to my tent, I rarely arrived at table with my breakfast cornflakes intact. Neither did I ever put fork to an egg without the fatty cooking medium having congealed to a solid around it. Much of my food at Paramali was either cooled by or gone with the wind. Clearly, the much touted declaration of Napoleon about an army marching on its stomach comes from his being used to essentially French cuisine.

. ![]()