Royal Corps of Signals

Dud's

Army.

Chapter

9

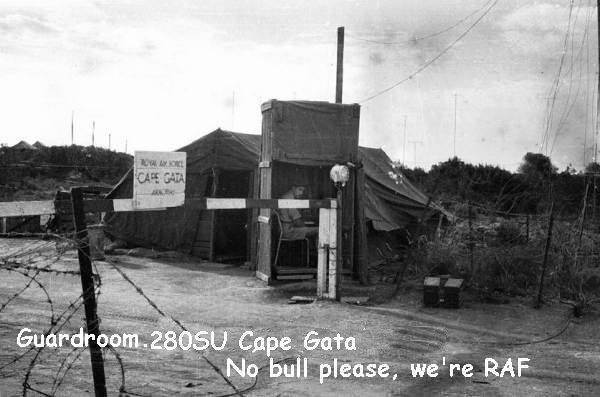

Cape Gata

We

did not have long to marvel at the crystal air of Episkopi. Next morning we

were advised to book out a Sten from the armoury and make ourselves ready for

a journey by road to Cape Gata, an isolated Signals unit attached to an isolated

RAF-operated radar installation cryptically identified as 280 SU. It was located

on the extreme southerly tip of the island. It sounded to me like Lands End

in Cornwall. Because of my stripes, I suppose, I was the one who signed out

the gun and magazine but I pushed the articles across to Jack as soon as they

came over the counter. He didn’t argue, which was a relief to me.

We

did not have long to marvel at the crystal air of Episkopi. Next morning we

were advised to book out a Sten from the armoury and make ourselves ready for

a journey by road to Cape Gata, an isolated Signals unit attached to an isolated

RAF-operated radar installation cryptically identified as 280 SU. It was located

on the extreme southerly tip of the island. It sounded to me like Lands End

in Cornwall. Because of my stripes, I suppose, I was the one who signed out

the gun and magazine but I pushed the articles across to Jack as soon as they

came over the counter. He didn’t argue, which was a relief to me.

We boarded an open-backed truck, with a wooden box for Jack to sit on. Jack would have been the first to agree that he did not quite cut the cavalier figure our previous day’s Bren-gun toting escort achieved but he took his riding-shotgun duty with a good grace. I sat on the truck’s floor nearby, tucked against the back of the cab, my head just high enough above the side walls to offer a terrorist’s bullet a difficult target. I had to sit up so that I could watch one side of the road while Jack attended to the other. A sergeant and driver came with us, the former advising us to bang on the cab rear window if we saw any trouble. In the usual hell-for-leather style we were off, hammering along like a fire engine. One had to admire the Army drivers. I’d already decided that theirs was to be my driving style once I got my civvy licence. Dad would lend me the car.

We had not gone more than a dozen miles and were passing through the scrubby hills where I’d thought the day before what perfect cover they offered to terrorist ambushers. Coming to a straight bit the driver gave it all he had, probably calibrating the speedo for full scale deflection. Without warning Jack’s beret blew off. It took a couple of spins through our slipstream and landed in the road. We were flying. Jack looked at me in horror, his hair a mess. I didn’t want him looking at me but at the danger areas we were passing, now going by unregarded, perfect cover for an ambush or I was a Dutchman.

"Don't worry about it," I shouted,"Buy another one."

Jack's look of horror changed to one of outrage.

"Not on your life," Jack countered.

Jack could be a stubborn bugger when he wanted to but being a Scot he was most likely considering the cost of a new one, or, being vain, the time it takes to get a beret looking non-nig-nog rather than remaining something like Picasso would wear. Without another word said he leaned over and beat a tattoo on the cab window.

The effect was instant and electric. We came to a screaming halt. One could smell the burned tyre rubber and see the smoke rising. The sergeant leapt out of the cab brandishing aloft an enormous pistol. He was yelling and dodging about, his back to us and calling over his shoulder, trying to look everywhere all at once. We caught occasional glimpses of his head and rolling eyes as he went bobbing about around the truck. I assumed this behaviour to be a combat-zone, Army, defensive manoeuvre. He certainly did not present an easy target. Each time he bobbed he would call out:

"What is it?... Where is 'e... What?... Where? for Chrissake...Where is the baastud?"

Jack sat on his box, wilting in the sun. Not finding any "baastuds" or "bomb lobbers" attacking us the sergeant, fully erect by this time and breathing hard, turned his red face and rolling eyes toward us baastuds.

"Ma hat blew off," reported Jack, attempting a combing of his hair with his free hand's worth of fingers. Jack was fanatical about personal tidiness.

Finding his pistol still at hand, so to speak, and declining to use it on us, the sergeant savagely gestured with it for Jack to head back to where his beret lay, still discernable, a tiny dark blip on the shining surface of the road. Within the enclosing hills it was as quiet as death. Jack trotted off down the road, a good fifty yards to go. Surprised the driver did not reverse the truck back, I was thinking that the terrorists would never get a better chance of an ambush than this. But they failed to capitalise.

I held the Sten, regarding the bushes sternly as Jack trotted back, returning it to him as he, re-hatted, regained his rearguard position on the wooden box. His beret, now seriously adjusted for Army driving, looked like a shower cap with a brooch. It did occur to me that thus attired Jack would not so easily be recognised as a British soldier and that the puzzlement might be enough to delay a terrorist shooter sufficiently for us to speed by. We burned more rubber as we took off. I badly wanted to have a good laugh with Jack about the comical side of it but since his face and features could be seen through the cab’s rear mirror and the prospect of an ambush down the road still prevailed we held it in until later. Then we laughed like hell. By way of a bonus we found to our delight that our destination that day was as good a place to laugh as any. We laughed while at Cape Gata more times than anywhere.

Cape

Gata was an unlikely paradise, but I could not have designed a better place

to be abroad in. It was so good to live there I have often though it a pity

my entire life was not spent there. At Cape Gata time stopped still. At Cape

Gata one did not think of time, certainly not as it applied to growing older.

If anything, at Cape Gata we grew younger.

Cape

Gata was an unlikely paradise, but I could not have designed a better place

to be abroad in. It was so good to live there I have often though it a pity

my entire life was not spent there. At Cape Gata time stopped still. At Cape

Gata one did not think of time, certainly not as it applied to growing older.

If anything, at Cape Gata we grew younger.

Our duties comprised maintaining a small transmitting facility, the radios and telephone equipment housed in a hut the size of a garden shed. The only aid to cooling the interior of the place came from openable side windows and a stable door so we perspired a bit at our work station, even when sitting and reading a book. Telephone lines from the RAF radar installations arrived at our hut and disappeared for connection into the line equipment cabinets. From there came lines we could patch into our AN/TRC radio sets which performed the necessary signal metamorphosis allowing voice transmission via any one of a half dozen antennae erected outside. Regular telephone lines did cross the island but the terrorists had taken to blowing them up. The hut and antennae lay at the western edge of camp, the latter being all under canvas except for the cookhouse, washhouse and toilets. The NAAFI was in the scruffiest of all tents, looking something like the abandoned marquee of a gone-broke circus. It was much the same within.

The main receiving point for our radio signals was Nicosia where the radar plots were routed to appropriate monitoring stations. I was told that if a plane took off in Egypt Nicosia would know about it. Our Signals linemen’s equipment worked well until it rained hard, always causing faults then that had to be fixed immediately. Out on an isolated cape with three hundred unarmed men at risk the phones were crucial, so faults of any kind were dealt with instantly, irrespective of the duty roster. Why we never were attacked by a commando type assault from the sea I’ll never know. We were vulnerable alright but our enemy must have lacked the necessary resources.

Our facility, including the revolving radar scanners ranged along the cliff edges like a strip of giant, primitive icons, functioned twenty four hours a day, seven days a week. Weekends and days were wiped from the conventional calendar and metamorphosed into an endless stream of hours. Overnight the names of each day of the week became anachronisms. Only the divisions of daylight and dark remained as recognisable entities, and then only because our world still belonged more to nature than to man. RAF and Army all worked shifts but meals were still served at regular times. One could always ask Albert The Lone Army Cook for a sandwich.

The complete Cape Gata Signals detachment comprised two Linemen, three Radio Relay Techs and a regular army Corporal, insufficient in numbers to even fill two tents. We did no guard duty, attended no camp parades and did no fatigues; the RAF took care of all that. The parade we did attend was for pay, and in formal uniform we walked the dusty road to Akrotiri and back every couple of weeks. Within days of arriving at Gata we had a four-day shift system worked out. Each technician, in sequence, would work his first day mornings, second day afternoons, third day all night and fourth day off. Jack and I arranged the sequence so that we got two days off at the same time. Our corporal took an occasional share of the shift. One slept in the equipment hut through one’s night shift. We had one of those spring-steel, rod-and-canvas arrangements that kept our perspiring bodies a few inches off the floor. Rarely were we awakened to do anything more than re-patch or answer a call from another Signals unit that were dotted around the southern coast. By sleeping on duty, the next day was not lost from having catch up on sleep. Off-duty time was precious.

The

AN/TRC radio sets were virtually trouble free. Occasionally some sort of protocol

demanded we change a crystal oscillator housed in a little encasement within

the radio we called an oven, a temperature controlling arrangement to keep the

Mhz frequency from wandering. Our unit officer would call in at the camp to

deliver the crystal. Where in Akrotiri our officer was specifically housed I

never learned. He manifested no personal interest in us or our doings, not on

our arrival, not at Christmas, not at Easter, not on one’s birthday, not

on his birthday, not on V.E. day, not at one’s departure, not at his departure,

not ever. We exchanged no words, that officer and I, only crystals and pay packets,

for which I was required to salute the miserable bugger. I remember him only

as being there. Most definitely the only humanly-sensible officer I ever met

or had any sort of truck with was Captain Macintyre of 4 TR and he made up for

the rest of them.

The camp housed a couple of hundred or more of RAF blokes, all occupying four-man tents arranged in straight lines east to west. We lived among them but were not of them. There was just enough room for a man to squeeze between the stretch of the side-ropes working against a central tent pole, thus keeping each tent upright and tethered to the ground. Every tent had a fly-sheet protecting the tent proper from the fierce sunlight, and the torrents of winter rain. Most of the tents had side boards about four feet high. It was in these nail-ups the bedbugs prospered. There were no mosquitoes. It became the business of the occupants to keep the tent in good shape. At the east end of the tent lines in full view of the radar sets a football pitch had been improvised, more than likely by the Scots. At Gata I came to learn and appreciate how much the Scots love football, all except Jack, of course, who couldn‘t care less. He was athletic enough, and swam like a fish, but to my knowledge he never kicked a ball - not during the two years I knew him. The pitch was pretty lumpy and stony, like Scotland in places. Not an easy place to fall down on and we scraped our knees badly.

The sores on one’s knees from falling down at football would not easily heal. I invented a method of curing them by pasting the sores over with the cigarette tissue paper one pulled from a new packet. Once the silver paper was peeled away the super-fine remnant could be placed over the weeping sore and within hours formed a scab that even resisted washing off during swimming once it had dried on. In this way one’s knees healed far more quickly.

No-one enjoyed a pick-up game of soccer more than me. At work where I started pre-apprentice down Penarth Road in Cardiff and then not long after on Bellott’s Road in Bath we played every dinner hour, a half hour game up and down the road with our steel-toed work-boots and a devil-take-the-hindmost attitude. At Cape Gata we played in the stony dirt. I wore out two pairs of football boots during the sixteen months playing there. In a pick-up game one gets to play a variety of positions and from these games I was able to improve the facility of my left foot enough to eventually take a corner kick from either side of the field.

None of the other army fellows played football so I got to make friends with the RAF blokes that way. I changed my opinion of them being a pansy lot; what rubbish goes around under the name of myth and rumour. I found myself in the toughest and best of company. It is almost impossible to impart what a wealth of character was to be found at that camp. It was a good feeling to be part of the crowd and to contribute to it like at 1 TR.

Of course the distraction of girls was absent, and in its place the distraction of no-girls. This latter was harder on the married men, Pete in my tent for one. He had a baby he hadn’t held or seen. I did not like being cut off from the other half like that but there was no choice in the matter. The proximity of the sea, the sun, the character of our close and wider company and the inner desire to do provided enough diversion if one went at it hard enough. This I did. And ironically, I was in the Army but my camp was RAF. It was the best of both worlds.

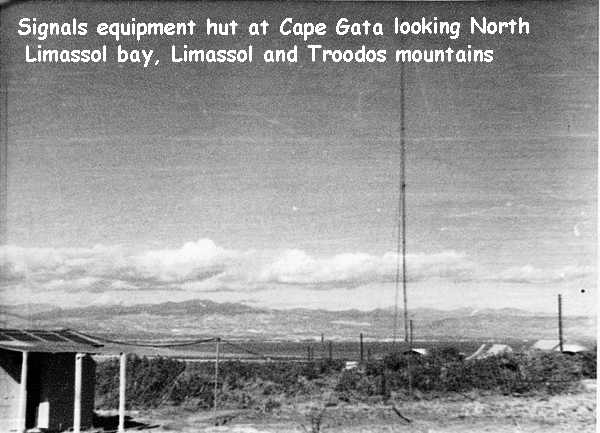

The great bay of Limassol curved like a scimitar away to the east. Each day we would see the returning Canberra bombers come flocking westward in across the bay to sink like grey geese down into Akrotiri. Far to the north ranged the jagged Troodos mountains where Colonel Grivas was said to be hiding. British soldiers had died up there, some burned alive in the forest set afire by the terrorists. But the world of wars and skirmishes lay at a safe distance from us. We remained isolated, a tiny outpost, ant-like in the great scheme of things, receiving and sending our secret signals from our fragile antennae. In order for our AN/TRC transmissions to reach Nicosia we were somehow able transmit either through or between the Troodos Mountains, which went against Army theory, leading to a technical investigation which typically went nowhere. We found we could transmit far more effectively through rock than over open water, but never did any serious investigating to find out why.

Bondos-bushed, lizard-infested, desert-like terrain immediately surrounded us on three sides. Our backs were to the coast with a short path linking the camp gate to the water‘s edge, our one single track to the outside world, the blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea. The swimming was superb. There was a great spread of flat rock handy for drying off or dozing on. The rock was broad and flat enough to practise running dives and cannonballs. Jack and I found ourselves posted to a kind of holiday camp, a paradise for boy soldiers. Being rendered homeless, rankless and braveless we adopted Gata in much the same way Peter Pan and the Lost Boys adopted Neverland. There, one could never be friendless.

They took my stripes at the first pay parade: a couple of indignities served coincidentally, basically a Machiavellian procedure. I am reminded that on arrival, an officer in Nicosia had assured Jack and I we should expect promotions in the near future. He was right about us expecting them which we did all the time we were there but promotion never arrived. This was just as well as our 280 SU dance cards were rapidly filling with appointments to partner all kinds of extra-curricular activities.

. ![]()